In October 2013, three young friends living in the Washington DC area — a male-female couple and a male friend — went out to a number of local bars to celebrate a birthday. The friends drank copiously, and then returned to a small studio apartment at 2 a.m. An hour later, one of the men stabbed his male friend to death. When police arrived, they found the surviving male covered in blood, with the floor and wall also covered in blood. “I caught my buddy and my girl cheating,” said the man. “I killed my buddy.” The man was subsequently found guilty of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

How did this happen? Was murder inevitable? It seems unlikely. The killing was not pre-planned. No one in the group had a prior record of violence or criminal activity. All three friends were well-educated and successful, with bright futures ahead of them. It’s true that all were extremely drunk, but drunkenness very rarely leads to murder.

This case is noteworthy, not because murders are unusual — murders happen all the time — but because this particular murder seems to have been completely unpredictable. It’s the normality of the persons and circumstances that disturbs the conscience. Under slightly different circumstances, the murder would not have happened at all, and all three would conceivably have lived long, happy lives.

Most of us are law-abiding citizens. We believe we are good, and despise thieves, rapists, and murderers. But what happens when the normal conditions under which we live change, when we are humiliated or outraged, when there is no security for our lives or property, when our opportunities for happiness are snatched from us for no good reason? How far will we go to avenge ourselves, and what violence will we justify in order to restore our perceived notion of justice?

The conflict between good and evil tendencies within human beings is a frequent theme in both philosophy and religion. However, philosophy has had a tendency to attribute evil tendencies within humanity to a deficiency of reason. In the view of many philosophers, reason alone should be able to establish that human rights are universal, and that impulses to violence, conquest, and enslavement are irrational. Furthermore, they argue that when reason establishes its dominance over the passions within human beings, societies become freer and more peaceful. (Notably, the great philosophers David Hume and Adam Smith rejected this argument.)

The religious interpretation of the conflict between good and evil, on the other hand, is based more upon myth and faith. And while the myths of religion are not literally accurate in terms of history or science, these myths often have insights into the inner turmoil of human beings that are lost in straightforward descriptions of fact and an emphasis on rationality.

The Christian scholar Paul Elmer More argued in his book, The Religion of Plato, that the dualism between good and evil within the human soul was very effectively described by the Greek philosopher Plato, but that this description relied heavily on the picturesque elements of myth, as found in the The Republic, Laws, Timaeus, and other works. In Plato’s view, there was a struggle within all human beings between a higher nature and a lower nature, the higher nature being drawn to a vision of ideal forms and the lower nature being dominated by the flux of human passions and desires. According to More,

It is not that pleasure or pain, or the desires and emotions connected with them, are totally depraved in themselves . . . but they contain the principle of evil in so far as they are radically unlimited, belonging by nature to what in itself is without measure and tends by inertia to endless expansion. Hence, left to themselves, they run to evil, whereas under control they may become good, and the art of life lies in the governing of pleasure and pain by a law exterior to them, in a man’s becoming master of himself, or better than himself. (pp. 225-6)

What are some of the myths Plato discusses? In The Republic, Plato tells the story of Gyges, a lowly shepherd who discovers a magic ring that bestows the power of invisibility. With this invisibility, Gyges is able to go wherever he wants undetected, and to do what he wants without anyone stopping him. Eventually, Gyges kills the king of his country and obtains absolute power for himself. In discussing this story, Glaucon, a student of Socrates, argues that with the awesome power of invisibility, no man would be able to remain just, in light of the benefits one could obtain. However, Socrates responds that being a slave to one’s desires actually does not bring long-term happiness, and that the happy man is one who is able to control his desires.

In the Phaedrus, Plato relates the dialogue between Socrates and his pupil Phaedrus on whether friendship is preferable to love. Socrates discusses a number of myths throughout the dialogue, but appears to use these myths as metaphorical illustrations of the internal struggle within human beings between their higher and lower natures. It is the nature of human beings, Socrates notes, to pursue the good and the beautiful, and this pursuit can be noble or ignoble depending on whether reason is driving one toward enlightenment or desire takes over and drives one to excessive pleasure-seeking. Indeed, Socrates describes love as a type of “madness” — but he argues that this madness is a source of inspiration that can result in either good or evil depending on how one directs the passions. Socrates proceeds to employ a figurative picture of a charioteer driving two horses, with one horse being noble and the other ignoble. The noble horse pulls the charioteer toward heaven, while the ignoble horse pulls the charioteer downward, toward the earth and potential disaster. Even so, the human being in love is influenced by the god he or she follows; the followers of Ares, the god of war, are inclined to violence if they feel wronged by their lover; the followers of Zeus, on the other hand, use love to seek philosophical wisdom.

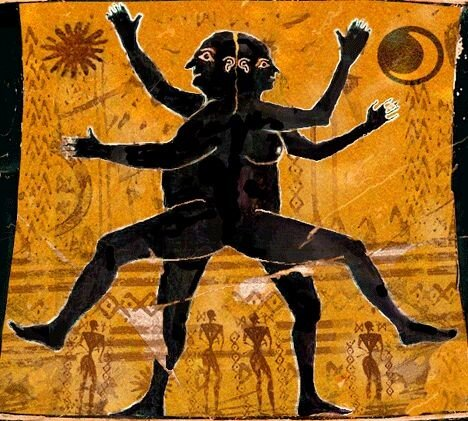

The nature and purpose of love is also discussed in the Symposium. In this dialogue, Socrates relates a fantastical myth about human beings originally being created with two bodies attached at the back, with two heads, four arms, and four legs. These beings apparently threatened the gods, so Zeus cut the beings in two; henceforth, humans spent their lives trying to find their other halves. Love inspires wisdom and courage, according to the dialogue, but only when it encourages companionship and the exchange of knowledge, and is not merely the pursuit of sexual gratification.

Illustration of the original humans described in Plato’s Symposium:

In the Timaeus, Plato discusses the creation of the universe and the role of human beings in this universe. Everything proceeds from the Good, argued Plato. However, the Good is not some lifeless abstraction, but a power with a dynamic element. According to More, Plato gave the name of God to this dynamic element. God fashions the universe according to an ideal pattern, but the end result is always less than perfect because of the resistance of the materials and the tendency of material things to always fall short of their perfect ends.

Plato argues that there are powers of good and powers of evil in the universe — and within human beings — and Plato personifies these powers as gods or daemons. There is a struggle between good and evil that all humans participate in, and all are subject to judgment at the ends of their lives (Plato believed in reincarnation and posited that deeds in one’s recent life determined one’s station in the next life.) Here, we see myth and faith enter again into Plato’s philosophy, and More defends the use of these stories and symbols as a means of illustrating the dramas of moral conflict:

In this last stage the essential truth of philosophy as a concern of the individual soul, is rendered vivid and convincing by clothing it in the imaginative garb of fiction — fiction which may yet be a veil, more or less transparent, through which we behold the actual events of the spirit world; and this aid of the imagination is needed just because the dualism of the human consciousness cannot be grasped by the reason, demands indeed a certain abatement of that rationalizing tendency of the mind which, if left to itself, inevitably seeks its satisfaction in one or the other form of monism. (p. 199)

What’s fascinating about Plato’s use of myths in philosophy is that while he recognizes that many of the myths are literally dubious or false, they seem to point to truths that are difficult or impossible to express in literal language. Love really does seem to be a desire to unite with one’s missing half, and falling in love really is akin to madness, a madness that can lead to disaster if one is not careful. Humankind does seem to be afflicted by an internal struggle between a higher, noble nature and a lower nature, with the lower nature inclined to self-centeredness and grasping for ever more wealth, power, and pleasure.

Plato had enormous influence on Western civilization, but More argues that the successors to Plato erred by abandoning Plato’s use of myth to illustrate the duality of human nature. Over the years, Greek philosophy became increasingly rationalistic and prone to a monism that was unable to cope with the reality of human dualism. (For an example of this extreme monism, see the works of Plotinus, who argued for an abstract “One” as the ultimate source of all things.) Hence, argued More, Christianity was in fact the true heir of Platonism, and not the Greek philosophers that came after Plato.

Myth is “the drama of religion,” according to More, not a literally accurate description of a sequence of events. Reason and philosophy can analyze and discuss good and evil, but to fully understand the conflict between good and evil, within and between human beings, requires a dramatic depiction of our swirling, churning passions. In More’s words, “A myth is false and reprehensible in so far as it misses or distorts the primary truth of philosophy and the secondary truth of theology; it becomes more probable and more and more indispensable to the full religious life as it lends insistence and reality to those truths and answers to the daily needs of the soul.” (p. 165) The role of Christian myths in illustrating the dramatic conflict between good and evil will be discussed in the next essay.