In my previous post, I addressed the debate between Christians and secular rationalists on the origins of the modern Western idea of human rights, with Christians attributing these rights to Christianity, whereas secular rationalists credited human reason. While acknowledging the crimes committed by the Christian churches in history, I also expressed skepticism about the ability of reason alone to provide a firm foundation for human rights.

In the second part of this essay, I would like to explore the idea that religion has a deep, partly subconscious, influence on culture and that this influence maintains itself even when people stop going to religious services, stop reading religious texts, and even stop believing in God. (Note: Much of what I am about to say next has been inspired by the works of the Christian theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who has covered this issue in his books, The Nature and Destiny of Man and The Self and the Dramas of History.)

___________________________

What exactly is religion, and why does it have a deep impact on our culture and thinking? Nearly all of today’s major existing religions date back from 1300 to 4000 years ago. In some respects, these religions have changed, but in most of their fundamentals, they have not. As such, there are unattractive elements in all of these religions, originating in primitive beliefs held at a time when there was hardly any truly scientific inquiry. As a guide to history, religious texts from this era are extremely unreliable; as a guide to scientific knowledge of the natural world, these religions are close to useless. So why, then, does religion continue to exercise a hold on the minds of human beings today?

I maintain that religion should be thought of primarily as a Theory of the Good. It is a way of thinking that does not (necessarily) result in truthful journalism and history, does not create accurate theories of causation, and ultimately, cares less about what things are really like and more about what things should be like.

As Robert Pirsig has noted, all life forms seek the Good, if only for themselves. They search for food, shelter, warmth, and opportunities for reproduction. More advanced life forms pursue all these and also may seek long-term companionship, a better location, and a more varied diet. If life forms can fly, they may choose to fly for the joy of it; if they can run fast, they may run for the joy of it.

Human beings have all these qualities, but also one more: with our minds, we can imagine an infinite variety of goods in infinite amounts; this is the source of our endless desires. In addition, our more advanced brains also give us the ability to imagine broadened sympathies beyond immediate family and friends, to nations and to humankind as a whole; this is the source of civilization. Finally, we also gain a curiosity about the origin of the world and ourselves and what our ultimate destiny is, or should be; this is the source of myths and faith. It is these imagined, transcendent goods that are the material for religion. And as a religion develops, it creates the basic concepts and categories by which we interpret the world.

There are many similarities among all the world’s religions in what is designated good and what is designated evil. But there are important differences as well, that have resulted in cultural clashes, sometimes leading to mild disagreements and sometimes escalating into the most vicious of wars. For the purpose of this essay, I am going to avoid the similarities among religions and discuss the differences.

Warning: Adequately covering all of the world’s major religions in a short essay is a hazardous enterprise. My depth of knowledge on this subject is not that great, and I will have to grossly simplify in many cases. I merely ask the reader for tolerance and patience; if you have a criticism, I welcome comments.

The most important difference between the major religions revolves around what is considered to be the highest good. This highest good seems to constitute a fundamental dividing line between the religions that is difficult to bridge. To make it simple, let’s summarize the highest good of each religion in one word:

Judaism – Covenant

Christianity – Love

Islam – Submission (to God)

Buddhism – Nirvana

Hinduism – Moksha

Jainism – Nonviolence (ahimsa)

Confucianism – Ren (Humanity)

Taoism – Wu Wei (inaction)

How does this perception of the highest good affect the nature of a religion?

Judaism: With only about 15 million adherents today, Judaism might appear to be a minor religion — but in fact, it is widely known throughout the world because of its huge influence on Christianity and Islam, which have billions of followers and have borrowed greatly from Judaism. Fundamental to Judaism is the idea of a covenant between God and His people, in which His people would follow the commandments of God, and God in return would bless His people with protection and abundance. This sort of faith faced many challenges over the centuries, as natural disasters and defeat in war were not always closely correlated with moral failings or a breach of the covenant. Nevertheless, the idea that moral behavior brings blessings has sustained the Jews and made them successful in many occupations for thousands of years. The chief disadvantage of Judaism has been its exclusive ties to a particular nation/ethnic group, which has limited its appeal to the rest of the world.

Christianity: Originating in Judaism, Christianity made a decisive break with Judaism under Jesus, and later, St. Paul. This break consisted primarily in recognizing that the laws of the Jews were somehow inadequate in making people good, because it was possible for someone to follow the letter of the law while remaining a very flawed or even terrible human being. Jesus’ denunciations of legalists and hypocrites in the New Testament are frequent and scathing. The way forward out of this, according to Jesus, was to simply love others, without making distinctions of rank, ethnicity, or religion. This original message of Jesus, and his self-sacrifice, inspired many Jews and non-Jews and led to the gradual, but steadily accelerating, growth of this minor sect. The chief flaw in Christianity became apparent hundreds of years after the crucifixion, when this minority sect became socially and politically powerful, and Christians used their new power to violently oppress others. This stark hypocrisy has discredited Christianity in the eyes of many.

Islam: A relatively young monotheistic religion, Islam grew out of the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh century AD. It’s prophet, Muhammad, clearly borrowed from Judaism and Christianity, but rejected the exclusivity of Judaism and the status of Jesus as the son of God. The word “Islam” means submission, but contrary to some commentators, it means submission to God, not to Islam or Muslims, which would be blasphemous. The requirements of Islam are fairly rigorous, requiring prayers five times a day; there is also an extensive body of Islamic law that is relatively strict, though implemented unevenly in Islamic countries today, with Iran and Saudi Arabia being among the strictest. There is no denying that the birth of Islam sparked the growth of a great empire that supported an advanced civilization. In the words of Bernard Lewis, “For many centuries the world of Islam was in the forefront of human civilization and achievement.” (What Went Wrong? The Clash Between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East, p. 3) Today, the Islamic world lags behind the rest of the world in many respects, perhaps because its strict social rules and tradition inhibit innovation in the modern world.

Confucianism. Founded by the scholar and government official Confucius in the 6th century B.C., Confucianism can be regarded as a system of morals based on the concept of Ren, or humanity. Confucius emphasized duty to the family, honesty in government, and espoused a version of the Golden Rule. There is a great deal of debate over whether Confucianism is actually a religion or mainly a philosophy and system of ethics. In fact, Confucius was a practical man, who did not discuss God or the afterlife, and never proclaimed an ability to perform miracles. But his impact on Chinese civilization, and Asian civilization generally, was tremendous, and the values of Confucius are deeply embedded in Chinese and other Asian societies to this day.

Buddhism. Founded by Gautama Buddha in the 6th century B.C., Buddhism addressed the problem of human suffering. In the view of the Buddha, our suffering arises from desire; because we cannot always get what we want, and what we want is never permanent, the human condition is one of perpetual dissatisfaction. When we die, we a born into another body, to suffer again. The Buddha argued that this cycle of suffering and rebirth could be ended by following the “eightfold path” – right understanding, right thought, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. Following this path could lead one to nirvana, which is the extinguishing of the self and the end of the cycle of rebirth and suffering. While not entirely pacifistic, there are strong elements of pacifism in Buddhism and a large number of Buddhists are vegetarian. Many non-Buddhists, however, would dispute the premise that life is suffering and that the dissolving of the self is a solution to suffering.

Hinduism. The third largest religion in the world, Hinduism is also considered to be the world’s oldest religion, with roots stretching back more than 4000 years. However, Hinduism also consists of different schools with diverse beliefs; there are multiple written texts in the Hindu tradition, but no single unifying text, such as the Bible or the Quran. A Hindu can believe in multiple gods or one God, and the Hindu conception of God/s can also vary. There is even a Hindu school of thought that is atheistic; this school goes back thousands of years. There is a strong tradition of nonviolence (ahimsa) in Hinduism, which obviously inspired Gandhi’s campaign of nonviolent resistance against British colonial rule in the early twentieth century. The chief goal of Hindu practices is moksha, or liberation from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth — roughly similar to the concept of nirvana.

Jainism. Originating in India around 2500 years ago, the Jain religion posits ahimsa, or nonviolence, as the highest good and goal of life. Jains practice a strict vegetarianism, which even extends to certain dairy products which may harm animals and any vegetable that may harm insects if harvested. The other principles of Jainism include anekāntavāda (non-absolutism) and aparigraha (non-attachment). The principle of non-absolutism recognizes that the truth is “many-sided” and impossible to fully express in language, while non-attachment refers to the necessity of avoiding the pursuit of property, taking and keeping only what is necessary.

Taosim. Developed in the 4th century B.C., Taoism is one of the major religions in China, along with Confucianism and Buddhism. “Tao” can be translated as “the Way,” or “the One, which is natural, spontaneous, eternal, nameless, and indescribable. . . the beginning of all things and the way in which all things pursue their course.” Pursuit of the “Way” is not meant to be difficult or arduous or require sacrifice, as in other religions. Rather, the follower must practice wu wei, or effortless action. The idea is that one must act in accord with the cosmos, not fight or struggle against it. Taoism values naturalness, spontaneity, and detachment from desires.

Now, all these religions, including many I have not listed, have value. The monotheism of Judaism and its strict moralism was a stark contrast to the ancient pagan religions, which saw the gods as conflictual, cruel, and prone to immoral behavior. The moral disciplines of Islam invigorated a culture and created a civilization more advanced than the Christian Europe of the Middle Ages. Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism have placed strong emphasis on overcoming self-centeredness and rejecting violence. Confucianism has instilled the values of respect for elders, love of family, and love of learning throughout East Asia. Taoism’s emphasis on harmony puts a break on human tendencies to dominate and control.

What I would like to focus on now are the particular contributions Christianity has made to Western civilization and how Christianity has shaped the culture of the West in ways we may not even recognize, contrasting the influence of Christianity with the influence of the other major religions.

__________________________

Christianity has provided four main concepts that have shaped Western culture, concepts that retain their influence today, even among atheists.

(1) The idea of a transcendent good, above and beyond nature and society.

(2) An emphasis on the worth of the individual, above society, government, and nature.

(3) Separation of religion and government.

(4) The idea of a meaningful history, that is, an unfolding story that ends with a conclusion, not a series of random events or cycles.

Let’s examine each of these in detail.

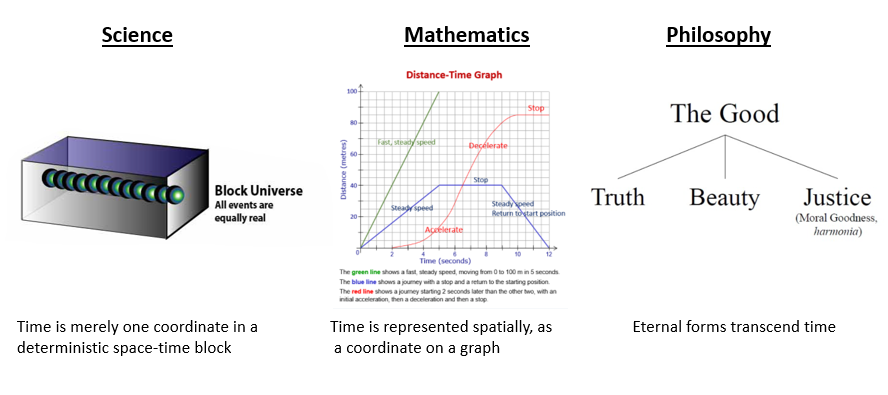

(1) Transcendent Good. I have written in some detail about the concept of transcendence elsewhere. In brief, transcendence refers to “the action of transcending, surmounting, or rising above . . . excelling.” To seek the transcendent is to aspire to something higher than reality. The difficulty with transcendence is that it’s not easily subject to empirical examination:

[B]ecause it seems to refer to a striving for an ideal or a goal that goes above and beyond an observed reality, transcendence has something of an unreal quality. It is easy to see that rocks and plants and stars and animals and humans exist. But the transcendent cannot be directly seen, and one cannot prove the transcendent exists. It is always beyond our reach.

Transcendent religions differ from pantheistic and panentheistic religions by insisting on the greater value or goal of an ideal state of being above and beyond the reality we experience. Since this ideal state is not subject to empirical proof, transcendent religions appear irrational and superstitious to many. Moreover, the dreamy idealism of transcendent religions often results in a fanaticism that leads to intolerance and religious wars. For these reasons, philosophers and scientists in the West usually prefer pantheistic interpretations of God (see Spinoza and Einstein).

The religions of India — Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism — have strong tendencies toward pantheism or panentheism, in which all existence is bound by a universal spirit, and our duty is to become one with this spirit. There is not a sharp distinction between this universal spirit and the universe or reality itself.

In China, Taoism rejects a personal God, while Confucianism is regarded by most as a philosophy or moral code than a religion. (The rational pragmatism of Chinese religion is probably why China had no major religious wars until a Chinese Christian in the 19th century led a rebellion on behalf of his “Heavenly Kingdom” that lasted 14 years and led to the deaths of tens of millions.)

And yet, there is a disadvantage in the rational pragmatism of Chinese religions — without a dreamy idealism, a culture can stagnate and become too accepting of evils. Chinese novelist Yan Lianke, who is an atheist, has remarked:

In China, the development of religion is the best lens through which to view the health of a society. Every religion, when it is imported to China is secularized. The Chinese are profoundly pragmatic. . . . What is absent in Chinese civilization, what we’ve always lacked, is a sense of the sacred. There is no room for higher principles when we live so firmly in the concrete. The possibility of hope and the aspiration to higher ideals are too abstract and therefore get obliterated in our dark, fierce realism.” (“Yan Lianke’s Forbidden Satires of China,” The New Yorker, 8 Oct 2018)

Now, Christianity is not alone in positing a transcendent good — Judaism and Islam also do this. But there are other particular qualities of Christianity that we must look to as well.

(2) Individual Worth.

To some extent, all religions value the individual human being. Yet, individual worth is central to Christianity in a way that is not found in other religions. The religions of India certainly value human life, and there are strong elements of pacifism in these religions. But these religions also tend to devalue individuality, in the sense that the ultimate goal is to overcome selfhood and merge with a larger spirit. Confucianism emphasizes moral duty, from the lowest members of society to the highest; individual worth is recognized, but the individual is still part of a hierarchy, and serves that hierarchy. In Taoism, the individual submits to the Way. In Islam, the individual submits to God. In Judaism, the idea of a Chosen People elevates one particular group over others (although this group also falls under the severe judgment of God).

Only under Christianity was the individual human being, whatever that person’s background, elevated to the highest worth. Jesus’ teachings on love and forgiveness, regardless of a person’s status and background, became central to Western civilization — though frequently violated in practice. Jesus’s vision of the afterlife emphasized not a merger with a universal spirit, but a continuance of individual life, free of suffering, in heaven.

3. Separation of religion and government.

Throughout history, the relation between religious institutions and government have varied. In some states, religion and government were unified, as in the Islamic caliphate. In most other cases, political authorities were not religious leaders, but priests were part of the ruling class that assisted the rulers. In China, Confucianism played a major role in the administrative bureaucracy, but Confucianism was a mild and rational religion that had no interest in pursuing and punishing heretics. In Judaism, rabbis often had some actual political power, depending on the historical period and location, but their power was never absolute.

Christianity originated with the martyrdom of a powerless man at the hands of an oppressive government and an intolerant society. In subsequent years, this minor sect was persecuted by the Roman empire. This persecution lasted for several hundred years; at no time during this period did Christianity receive the support, approval, or even tolerance of the imperial government.

Few other religions have originated in such an oppressive atmosphere and survived. China absorbed Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism without wars and extensive persecution campaigns. Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism grew out of the same roots and largely tolerated each other. Islam had its enemies in its early years, but quickly triumphed in a series of military campaigns that built a great empire. Even the Jews, one of the most persecuted groups in history, were able to practice their religion in their own state(s) for hundreds of years before military defeat and diaspora; in 1948, the Jews again regained a state.

Now, it is true that in the 4th century A.D., Christianity became the official state religion of the Roman empire, and the Christian persecution of pagan worshippers began. Over the centuries, the Catholic Church exercised enormous influence over the culture, economy, and politics of Europe. But by the 18th and 19th centuries, the idea of a strict separation between church and state became widely popular, first in America, then in Europe. While Christian churches fought this reduction in Christian political power and influence, the separation of Church and state was at least compatible with the origins of Christianity in persecution and martyrdom, and did not violate the core beliefs of Christianity.

4. A meaningful history.

The idea that history consists of a progressive movement toward an ideal end is not common to all cultures. Ancient Greeks and Romans saw history as a long decline from an original “Golden Age,” or they saw history as essentially cyclical, consisting of a never-ending rise and decline of various civilizations. The historical views of Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism were also cyclical.

It was Judaism, Christianity, and Islam that interpreted history as progressing toward an ideal end, a kingdom of heaven. But as a result of the Renaissance in the West, and then the Enlightenment, the idea of an otherworldly kingdom was dumped, and the ideal end of history became secularized. The German philosopher Hegel (1770-1831) interpreted history as a dialectic clash of ideas, moving toward its ultimate end, which was human freedom. (An early enthusiast for the French Revolution, Hegel once referred to Napoleon as the “world soul” on horseback.) Karl Marx took Hegel’s vision one step further, removing Hegel’s idealism and positing a “dialectical materialism” based on class conflict. This class conflict, according to Marx, would one day end in a final, bloody clash that would end class distinctions and bring about the full equality of human beings under communism.

Alas, these dreams of earthly utopia did not come to pass. Napoleon crowned himself emperor in 1804 and went to work creating a new dynasty and aristocracy with which to rule Europe. In the twentieth century, Communist regimes were extraordinarily oppressive everywhere they arose, killing tens of millions of people. Certainly, the idea of human equality was attractive, and political movements arose and took power based on these ideas. Yet the results were bloodshed and tyranny. Even so, when Soviet communism collapsed, the idea of a secular “end of history,” based on the thought of Hegel, became popular again.

According to the American Christian theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, the visions of Hegel and Marx were merely secular versions of Christianity, which failed because, while ostensibly dedicated to the principles of individual worth, equality, and historical progress, they could not overcome the essential fact of human sinfulness. In Christianity, this sinfulness was the basis for the prophecies in the Book of Revelation which foresaw a final battle between good and evil, requiring the intervention of God in order to achieve a final triumph of good.

According to Niebuhr, the fundamental error of all secular ideologies of historical progress was to suppose that the ability of human beings to reason could conquer tendencies to sinfulness in the same way that advances in science could conquer nature. This did not work, in Niebuhr’s view, because reason could be a tool of self-aggrandizement as well as selflessness, and was therefore insufficient to support universal brotherhood. The fundamental truth about human nature, that the Renaissance and the Enlightenment neglected, was that man is an unbreakable organic unity of mind, body, and spirit. Man’s increasing capacity to use reason resulted in new technologies and wealth but did not — and could not — overcome human tendencies to seek power. For this reason, human history was the story of the growth of both good and evil and not the triumph of good over evil. Only the intervention of God, through Christ, could bring the final fulfillment of history. Certainly, belief in this ultimate fulfillment requires a leap of faith — but whether or not one believes the Book of Revelation, it is hard to deny that human dreams of earthly utopia have been frustrated time and time again.

Perhaps at this point, you may agree with my general assessment of Christian ideas, and even find some similarities between Christian ideas and contemporary secular liberalism. Nevertheless, you may also conclude that the causal linkage between Christianity and modern liberalism has not been established. After all, the first modern liberal democracies did not emerge until nearly 1800 years after Christ. Why so long? Why did the Christian churches have such a long record of intolerance and contempt for liberal ideas? Why did the Catholic Church so often ally with monarchs, defend feudalism, and oppose liberal revolutions? Why did various Christian churches tolerate and approve of slavery for hundreds of years? I will address these issues in Part Three.