Robert Pirsig writes in Lila that Quality contains a dynamic good in addition to a static good. This dynamic good consists of a search for “betterness” that is unplanned and has no specific destination, but is nevertheless responsible for all progress. Once a dynamic good solidifies into a concept, practice, or tradition in a culture, it becomes a static good. Creativity, mysticism, dreams, and even good guesses or luck are examples of dynamic good in action. Religious traditions, laws, and science textbooks are examples of static goods.

Pirsig describes dynamic quality as the “pre-intellectual cutting edge of reality.” By this, he means that before concepts, logic, laws, and mathematical formulas are discovered, there is process of searching and grasping that has not yet settled into a pattern or solution. For example, invention and discovery is often not an outcome of calculation or logical deduction, but of a “free association of ideas” that tends to occur when one is not mentally concentrating at all. Many creative people, from writers to mathematicians, have noted that they came up with their best ideas while resting, engaging in everyday activities, or dreaming.

Dynamic quality is not just responsible for human creation — it is fundamental to all evolution, from the physical level of atoms and molecules, to the biological level of life forms, to the social level of human civilization, to the intellectual level of human thought. Dynamic quality exists everywhere, but it has no specific goals or plans — it always consists of spur-of-the-moment actions, decisions, and guesses about how to overcome obstacles to “betterness.”

It is difficult to conceive of dynamic quality — by its very nature, it is resistant to conceptualization and definition, because it has no stable form or structure. If it did have a stable form or structure, it would not be dynamic.

However the French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941) provided a way to think about dynamic quality, by positing change as the fundamental nature of reality. (See Beyond the “Mechanism” Metaphor in Physics.) In Bergson’s view, traditional reason, science, and philosophy created static, eternal forms and posited these forms as the foundation of reality — but in fact these forms were tools for understanding reality and not reality itself. Reality always flowed and was impossible to fully capture in any static conceptual form. This flow could best be understood through perception rather than conception. Unfortunately, as philosophy created larger and larger conceptual categories, philosophy tended to become dominated by empty abstractions such as “substance,” “numbers,” and “ideas.” Bergson proposed that only an intuitive approach that enlarged perceptual knowledge through feeling and imagination could advance philosophy out of the dead end of static abstractions.

________________________

The Flow of Time

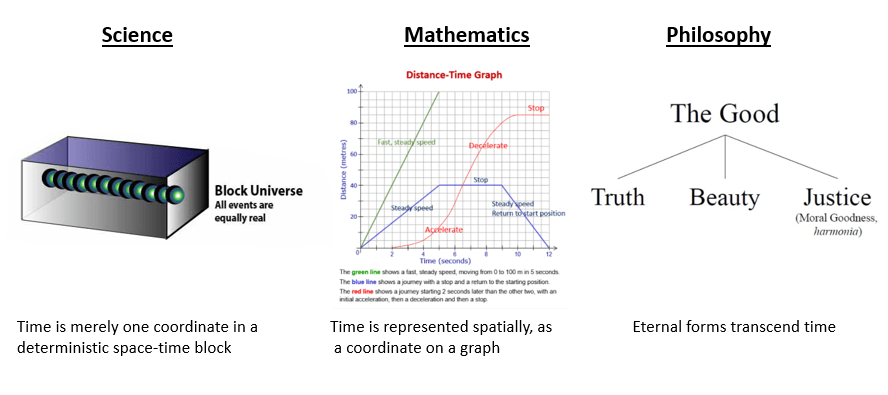

Bergson argued that we miss the flow of time when we use the traditional tools of science, mathematics, and philosophy. Science conceives of time as simply one coordinate in a deterministic space-time block ruled by eternal laws; mathematics conceives of time as consisting of equal segments on a graph; and philosophers since Plato have conceptualized the world as consisting of the passing shadows of eternal forms.

These may be useful conceptualizations, argues Bergson, but they do not truly grasp time. Whether it is an eternal law, a graph, or an eternal form, such depictions are snapshots of reality; they do not and cannot represent the indivisible flow of time that we experience. The laws of science in particular neglected the elements of indeterminism and freedom in the universe. (Henri Bergson once debated Einstein on this topic). The neglect of real change by science was the result of science’s ambition to foresee all things, which motivated scientists to focus on the repeatable and calculable elements of nature, rather than the genuinely new. (The Creative Mind, Mineola, New York: Dover, 2007, p. 3) Those events that could not be predicted were tossed aside as being merely random or unknowable. As for philosophy, Bergson complained that the eternal forms of the philosophers were empty abstractions — the categories of beauty and justice and truth were insufficient to serve as representations of real experience.

Actual reality, according to Bergson, consisted of “unceasing creation, the uninterrupted upsurge of novelty.” (The Creative Mind, p. 7) Time was not merely a coordinate for recording motion in a determinist universe; time was “a vehicle of creation and choice.” (p. 75) The reality of change could not be captured in static concepts, but could only be grasped intuitively. While scientists saw evolution as a combination of mechanism and random change, Bergson saw evolution as a result of a vital impulse (élan vital) that pervaded the universe. Although this vital impetus possessed an original unity, individual life forms used this vital impetus for their own ends, creating conflict between life forms. (Creative Evolution, pp. 50-51)

Biologists attacked Bergson on the grounds that there was no “vital impulse” that they could detect and measure. But biologists argued from the reductionist premise that everything could be explained by reference to smaller parts, and since there was no single detectable force animating life, there was no “vital impetus.” But Bergson’s premise was holistic, referring to the broader action of organic development from lower orders to higher orders, culminating in human beings. There was no separate force — rather entities organized, survived, and reproduced by absorbing and processing energy, in multiple forms. In the words of one eminent biologist, organisms are “resilient patterns . . . in an energy flow.” There is no separate or unique energy of life – just energy.

The Superiority of Perception over Conception

Bergson believed with William James that all knowledge originated in perception and feeling; as human mental powers increased, conceptual categories were created to organize and generalize what we (and others) discovered through our senses. Concepts were necessary to advance human knowledge, of course. But over time, abstract concepts came to dominate human thought to the point at which pure ideas were conceived as the ultimate reality — hence Platonism in philosophy, mathematical Platonism in mathematics, and eternal laws in science. Bergson believed that although we needed concepts, we also needed to rediscover the roots of concepts in perception and feeling:

If the senses and the consciousness had an unlimited scope, if in the double direction of matter and mind the faculty of perceiving was indefinite, one would not need to conceive any more than to reason. Conceiving is a make-shift when perception is not granted to us, and reasoning is done in order to fill up the gaps of perception or to extend its scope. I do not deny the utility of abstract and general ideas, — any more than I question the value of bank-notes. But just as the note is only a promise of gold, so a conception has value only through the eventual perceptions it represents. . . . the most ingeniously assembled conceptions and the most learnedly constructed reasonings collapse like a house of cards the moment the fact — a single fact rarely seen — collides with these conceptions and these reasonings. There is not a single metaphysician, moreover, not one theologian, who is not ready to affirm that a perfect being is one who knows all things intuitively without having to go through reasoning, abstraction and generalisation. (The Creative Mind, pp. 108-9)

In the end, despite their obvious utility, the conceptions of philosophy and science tend “to weaken our concrete vision of the universe.” (p. 111) But we clearly do not have God-like powers to perceive everything, and we are not likely to get such powers. So what do we do? Bergson argues that instead of “trying to rise above our perception of things” through concepts, we “plunge into [perception] for the purpose of deepening it and widening it.” (p. 111) But how exactly are we to do this?

Enlarging Perception

There is one group of people, argues Bergson, that have mastered the ability to deepen and widen perception: artists. From paintings to poetry to novels and musical compositions, artists are able to show us things and events that we do not directly perceive and evoke a mood within us that we can understand even if the particular form that the artist presents may never have been seen or heard by us before. Bergson writes that artists are idealists who are often absent-mindedly detached from “reality.” But it is precisely because artists are detached from everyday living that they are able to see things that ordinary, practical people do not:

[Our] perception . . . isolates that part of reality as a whole that interests us; it shows us less the things themselves than the use we can make of them. It classifies, it labels them beforehand; we scarcely look at the object, it is enough for us to know which category it belongs to. But now and then, by a lucky accident, men arise whose senses or whose consciousness are less adherent to life. Nature has forgotten to attach their faculty of perceiving to their faculty of acting. When they look at a thing, they see it for itself, and not for themselves. They do not perceive simply with a view to action; they perceive in order to perceive — for nothing, for the pleasure of doing so. In regard to a certain aspect of their nature, whether it be their consciousness or one of their senses, they are born detached; and according to whether this detachment is that of a particular sense, or of consciousness, they are painters or sculptors, musicians or poets. It is therefore a much more direct vision of reality that we find in the different arts; and it is because the artist is less intent on utilizing his perception that he perceives a greater number of things. (The Creative Mind, p. 114)

The Method of Intuition

Bergson argued that the indivisible flow of time and the holistic nature of reality required an intuitive approach, that is “the sympathy by which one is transported into the interior of an object in order to coincide with what there is unique and consequently inexpressible in it.” (The Creative Mind, p. 135) Analysis, as in the scientific disciplines, breaks down objects into elements, but this method of understanding is a translation, an insight that is less direct and holistic than intuition. The intuition comes first, and one can pass from intuition to analysis but not from analysis to intuition.

In his essay on the French philosopher Ravaisson, Bergson underscored the benefits and necessity of an intuitive approach:

[Ravaisson] distinguished two different ways of philosophizing. The first proceeds by analysis; it resolves things into their inert elements; from simplification to simplification it passes to what is most abstract and empty. Furthermore, it matters little whether this work of abstraction is effected by a physicist that we may call a mechanist or by a logician who professes to be an idealist: in either case it is materialism. The other method not only takes into account the elements but their order, their mutual agreement and their common direction. It no longer explains the living by the dead, but, seeing life everywhere, it defines the most elementary forms by their aspiration toward a higher form of life. It no longer brings the higher down to the lower, but on the contrary, the lower to the higher. It is, in the real sense of the word, spiritualism. (p. 202)

From Philosophy to Religion

A religious tendency is apparent in Bergson’s philosophical writings, and this tendency grew more pronounced as Bergson grew older. It is likely that Bergson saw religion as a form of perceptual knowledge of the Good, widened by imagination. Bergson’s final major work, The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1977) was both a philosophical critique of religion and a religious critique of philosophy, while acknowledging the contributions of both forms of knowledge. Bergson drew a distinction between “static religion,” which he believed originated in social obligations to society, and “dynamic religion,” which he argued originated in mysticism and put humans “in the stream of the creative impetus.” (The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, p. 179)

Bergson was a harsh critic of the superstitions of “static religion,” which he called a “farrago of error and folly.” These superstitions were common in all cultures, and originated in human imagination, which created myths to explain natural events and human history. However, Bergson noted, static religion did play a role in unifying primitive societies and creating a common culture within which individuals would subordinate their interests to the common good of society. Static religion created and enforced social obligations, without which societies could not endure. Religion also provided comfort against the depressing reality of death. (The Two Source of Morality and Religion, pp. 102-22)

In addition, it would be a mistake, Bergson argued, to suppose that one could obtain dynamic religion without the foundation of static religion. Even the superstitions of static religion originated in the human perception of a beneficent virtue that became elaborated into myths. Perhaps thinking that a cool running spring or a warm fire on the hearth as the actions of spirits or gods were a case of imagination run rampant, but these were still real goods, as were the other goods provided by the pagan gods.

Dynamic religion originated in static religion, but also moved above and beyond it, with a small number of exceptional human beings who were able to reach the divine source: “In our eyes, the ultimate end of mysticism is the establishment of a contact . . . with the creative effort which life itself manifests. This effort is of God, if it is not God himself. The great mystic is to be conceived as an individual being, capable of transcending the limitations imposed on the species by its material nature, thus continuing and extending the divine action.” (pp. 220-21)

In Bergson’s view, mysticism is intuition turned inward, to the “roots of our being , and thus to the very principle of life in general.” (p. 250) Rational philosophy cannot fully capture the nature of mysticism, because the insights of mysticism cannot be captured in words or symbols, except perhaps in the word “love”:

God is love, and the object of love: herein lies the whole contribution of mysticism. About this twofold love the mystic will never have done talking. His description is interminable, because what he wants to describe is ineffable. But what he does state clearly is that divine love is not a thing of God: it is God Himself. (p. 252)

Even so, just as the dynamic religion bases its advanced moral insights in part on the social obligations of static religion, dynamic religion also must be propagated through the images and symbols supplied by the myths of static religion. (One can see this interplay of static and dynamic religion in Jesus and Gandhi, both of whom were rooted in their traditional religions, but offered original teachings and insights that went beyond their traditions.)

Toward the end of his life, Henri Bergson strongly considered converting to Catholicism (although the Church had already placed three of Bergson’s works on its Index of Prohibited Books). Bergson saw Catholicism as best representing his philosophical inclinations for knowing through perception and intuition, and for joining the vital impetus responsible for creation. However, Bergson was Jewish, and the anti-Semitism of 1930s and 1940s Europe made him reluctant to officially break with the Jewish people. When the Nazis conquered France in 1940 and the Vichy puppet government of France decided to persecute Jews, Bergson registered with the authorities as a Jew and accepted the persecutions of the Vichy regime with stoicism. Bergson died in 1941 at the age of 81.

Once among the most celebrated intellectuals in the world, today Bergson is largely forgotten. Even among French philosophers, Bergson is much less known than Descartes, Sartre, Comte, and Foucault. It is widely believed that Bergson lost his debate with Einstein in 1922 on the nature of time. (See Jimena Canales, The Physicist and the Philosopher: Einstein, Bergson, and the Debate that Changed Our Understanding of Time, p. 6) But it is recognized today even among physicists that while Einstein’s conception of spacetime in relativity theory is an excellent theory for predicting the motion of objects, it does not disprove the existence of time and real change. It is also true that Bergson’s writings are extraordinarily difficult to understand at times. One can go through pages of dense, complex text trying to understand what Bergson is saying, get suddenly hit with a colorful metaphor that seems to explain everything — and then have a dozen more questions about the meaning of the metaphor. Nevertheless, Bergson remains one of the very few philosophers who looked beyond eternal forms to the reality of a dynamic universe, a universe moved by a vital impetus always creating, always changing, never resting.